Phaedo

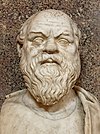

Phædo or Phaedo (/ˈfiːdoʊ/; Greek: Φαίδων, Phaidōn [pʰaídɔːn]), also known to ancient readers as On The Soul,[1] is one of the best-known dialogues of Plato's middle period, along with the Republic and the Symposium. The philosophical subject of the dialogue is the immortality of the soul. It is set in the last hours prior to the death of Socrates, and is Plato's fourth and last dialogue to detail the philosopher's final days, following Euthyphro, Apology, and Crito.

One of the main themes in the Phaedo is the idea that the soul is immortal. In the dialogue, Socrates discusses the nature of the afterlife on his last day before being executed by drinking hemlock. Socrates has been imprisoned and sentenced to death by an Athenian jury for not believing in the gods of the state (though some scholars think it was more for his support of "philosopher kings" as opposed to democracy)[2] and for corrupting the youth of the city.

By engaging in dialectic with a group of Socrates's friends, including the two Thebans, Cebes, and Simmias, Socrates explores various arguments for the soul's immortality in order to show that there is an afterlife in which the soul will dwell following death and, for couples and good people, be more at one with "every loving thing" and be more powerful than the Greek gods.[3] Phaedo tells the story that following the discussion, he and the others were there to witness the death of Socrates.

The Phaedo was first translated into Latin from Greek by Apuleius[4] but no copy survived, so Henry Aristippus produced a new translation in 1160.

Summary

[edit]The dialogue is told from the perspective of one of Socrates's students, Phaedo of Elis, who was present at Socrates's death bed. Phaedo relates the dialogue from that day to Echecrates, a Pythagorean philosopher.

Socrates offers four arguments for the soul's immortality:

- The Cyclical Argument, or Opposites Argument explains that Forms are eternal and unchanging, and as the soul always brings life, then it must not die, and is necessarily "imperishable". As the body is mortal and is subject to physical death, the soul must be its indestructible opposite. Plato then suggests the analogy of fire and cold. If the form of cold is imperishable, and fire, its opposite, was within close proximity, it would have to withdraw intact as does the soul during death. This could be likened to the idea of the opposite poles of magnets.

- The Recollection Argument, which is based on Plato's famous theory of recollection, explains that we possess some non-empirical knowledge (e.g. The Form of Equality) at birth, implying the soul existed before birth to carry that knowledge. Another account of the theory is found in Plato's Meno, although in that case Socrates implies anamnesis (previous knowledge of everything) whereas he is not so bold in Phaedo.

- The Affinity Argument explains that invisible, immortal, and incorporeal things are different from visible, mortal, and corporeal things. Our soul is of the former, while our body is of the latter, so when our bodies die and decay, our soul will continue to live.

- The Argument from Form of Life, or The Final Argument explains that the Forms, incorporeal and static entities, are the cause of all things in the world, and all things participate in Forms. For example, beautiful things participate in the Form of Beauty; the number four participates in the Form of the Even, etc. The soul, by its very nature, participates in the Form of Life, which means the soul can never die.

Some scholars have debated the accuracy of these names: for instance, David Ebrey has argued that the recollection argument should be titled 'the recollecting argument' because 'recollection' names the end-result of a process, whereas Plato is discussing the process of recollecting itself; he also has argued that the affinity argument should be called 'the kinship argument' instead because the argument is based on learning about the soul's nature from discussing its kin (i.e., the divine).[5]

Introductory conversation

[edit]The scene is set in Phlius where Echecrates who, meeting Phaedo, asks for news about the last days of Socrates. Phaedo explains why a delay occurred between his trial and his death, and describes the scene in a prison at Athens on the final day, naming those present. He tells how he had visited Socrates early in the morning with the others. Socrates's wife Xanthippe was there, but was very distressed and Socrates asked that she be taken away. Socrates relates how, bidden by a recurring dream to "make and cultivate music", he wrote a hymn and then began writing poetry based on Aesop's Fables.[6]

Socrates tells Cebes to "bid him (Socrates's friend Evenus) farewell from me; say that I would have him come after me if he be a wise man" Simmias expresses confusion as to why they ought hasten to follow Socrates to death. Socrates then states "... he, who has the spirit of philosophy, will be willing to die; but he will not take his own life." Cebes raises his doubts as to why suicide is prohibited. He asks, "Why do you say ... that a man ought not to take his own life, but that the philosopher will be ready to follow one who is dying?" Socrates replies that while death is the ideal home of the soul, man, specifically the philosopher, should not commit suicide except when it becomes necessary.[7]

Man ought not to kill himself because he possesses no actual ownership of himself, as he is actually the property of the gods. He says, "I too believe that the gods are our guardians, and that we men are a chattel of theirs". While the philosopher seeks always to rid himself of the body, and to focus solely on things concerning the soul, to commit suicide is prohibited as man is not sole possessor of his body. For, as stated in the Phaedo: "the philosopher more than other men frees the soul from association with the body as much as possible". Body and soul are separate, then. The philosopher frees himself from the body because the body is an impediment to the attainment of truth.[8]

Of the senses' failings, Socrates says to Simmias in the Phaedo:

Did you ever reach them (truths) with any bodily sense? – and I speak not of these alone, but of absolute greatness, and health, and strength, and, in short, of the reality or true nature of everything. Is the truth of them ever perceived through the bodily organs? Or rather, is not the nearest approach to the knowledge of their several natures made by him who so orders his intellectual vision as to have the most exact conception of the essence of each thing he considers?[9]

The philosopher, if he loves true wisdom and not the passions and appetites of the body, accepts that he can come closest to true knowledge and wisdom in death, as he is no longer confused by the body and the senses. In life, the rational and intelligent functions of the soul are restricted by bodily senses of pleasure, pain, sight, and sound.[10] Death, however, is a rite of purification from the "infection" of the body. As the philosopher prepares for death his entire life, he should greet it amicably and not be discouraged upon its arrival, for since the universe the gods created for us in life is essentially "good", why would death be anything but a continuation of this goodness? Death is a place where better and wiser gods rule and where the most noble souls serve in their presence: "And therefore, so far as that is concerned, I not only do not grieve, but I have great hopes that there is something in store for the dead ... something better for the good than for the wicked."[11]

The soul attains virtue when it is purified from the body: "He who has got rid, as far as he can, of eyes and ears and, so to speak, of the whole body, these being in his opinion distracting elements when they associate with the soul hinder her from acquiring truth and knowledge – who, if not he, is likely to attain to the knowledge of true being?"[12]

The Cyclical Argument

[edit]Cebes voices his fear of death to Socrates: "... they fear that when she [the soul] has left the body her place may be nowhere, and that on the very day of death she may perish and come to an end immediately on her release from the body ... dispersing and vanishing away into nothingness in her flight."[13]

In order to alleviate Cebes's worry that the soul might perish at death, Socrates introduces his first argument for the immortality of the soul. This argument is often called the Cyclical Argument. It supposes that the soul must be immortal since the living come from the dead. Socrates says: "Now if it be true that the living come from the dead, then our souls must exist in the other world, for if not, how could they have been born again?". He goes on to show, using examples of relationships, such as asleep-awake and hot-cold, that things that have opposites come to be from their opposite. One falls asleep after having been awake. And after being asleep, he awakens. Things that are hot came from being cold and vice versa. Socrates then gets Cebes to conclude that the dead are generated from the living, through life, and that the living are generated from the dead, through death. The souls of the dead must exist in some place for them to be able to return to life. Socrates further emphasizes the cyclical argument by pointing out that if opposites did not regenerate one another, all living organisms on Earth would eventually die off, never to return to life.[14]

The Recollection Argument

[edit]Cebes realizes the relationship between the Cyclical Argument and Socrates' Theory of Recollection. He interrupts Socrates to point this out, saying:

... your favorite doctrine, Socrates, that our learning is simply recollection, if true, also necessarily implies a previous time in which we have learned that which we now recollect. But this would be impossible unless our soul had been somewhere before existing in this form of man; here then is another proof of the soul's immortality.[15]

Socrates' second argument, the Theory of Recollection, shows that it is possible to draw information out of a person who seems not to have any knowledge of a subject prior to his being questioned about it (a priori knowledge). This person must have gained this knowledge in a prior life, and is now merely recalling it from memory. Since the person in Socrates' story is able to provide correct answers to his interrogator, it must be the case that his answers arose from recollections of knowledge gained during a previous life.[16]

The Affinity Argument

[edit]Socrates presents his third argument for the immortality of the soul, the so-called Affinity Argument, where he shows that the soul most resembles that which is invisible and divine, and the body resembles that which is visible and mortal. From this, it is concluded that while the body may be seen to exist after death in the form of a corpse, as the body is mortal and the soul is divine, the soul must outlast the body.[17]

As to be truly virtuous during life is the quality of a great man who will perpetually dwell as a soul in the underworld. However, regarding those who were not virtuous during life, and so favored the body and pleasures pertaining exclusively to it, Socrates also speaks. He says that such a soul is:

... polluted, is impure at the time of her departure, and is the companion and servant of the body always and is in love with and bewitched by the body and by the desires and pleasures of the body, until she is led to believe that the truth only exists in a bodily form, which a man may touch and see, and drink and eat, and use for the purposes of his lusts, the soul, I mean, accustomed to hate and fear and avoid that which to the bodily eye is dark and invisible, but is the object of mind and can be attained by philosophy; do you suppose that such a soul will depart pure and unalloyed?[18]

Persons of such a constitution will be dragged back into corporeal life, according to Socrates. These persons will even be punished while in Hades. Their punishment will be of their own doing, as they will be unable to enjoy the singular existence of the soul in death because of their constant craving for the body. These souls are finally "imprisoned in another body". Socrates concludes that the soul of the virtuous man is immortal, and the course of its passing into the underworld is determined by the way he lived his life. The philosopher, and indeed any man similarly virtuous, in neither fearing death, nor cherishing corporeal life as something idyllic, but by loving truth and wisdom, his soul will be eternally unperturbed after the death of the body, and the afterlife will be full of goodness.[19]

Simmias confesses that he does not wish to disturb Socrates during his final hours by unsettling his belief in the immortality of the soul, and those present are reluctant to voice their skepticism. Socrates grows aware of their doubt and assures his interlocutors that he does indeed believe in the soul's immortality, regardless of whether or not he has succeeded in showing it as yet. For this reason, he is not upset facing death and assures them that they ought to express their concerns regarding the arguments. Simmias then presents his case that the soul resembles the harmony of the lyre. It may be, then, that as the soul resembles the harmony in its being invisible and divine, once the lyre has been destroyed, the harmony too vanishes, therefore when the body dies, the soul too vanishes. Once the harmony is dissipated, we may infer that so too will the soul dissipate once the body has been broken, through death.[20]

Socrates pauses, and asks Cebes to voice his objection as well. He says, "I am ready to admit that the existence of the soul before entering into the bodily form has been ... proven; but the existence of the soul after death is in my judgment unproven." While admitting that the soul is the better part of a man, and the body the weaker, Cebes is not ready to infer that because the body may be perceived as existing after death, the soul must therefore continue to exist as well. Cebes gives the example of a weaver. When the weaver's cloak wears out, he makes a new one. However, when he dies, his more freshly woven cloaks continue to exist. Cebes continues that though the soul may outlast certain bodies, and so continue to exist after certain deaths, it may eventually grow so weak as to dissolve entirely at some point. He then concludes that the soul's immortality has yet to be shown and that we may still doubt the soul's existence after death. For, it may be that the next death is the one under which the soul ultimately collapses and exists no more. Cebes would then, "... rather not rely on the argument from superior strength to prove the continued existence of the soul after death."[21]

Seeing that the Affinity Argument has possibly failed to show the immortality of the soul, Phaedo pauses his narration. Phaedo remarks to Echecrates that, because of this objection, those present had their "faith shaken," and that there was introduced "a confusion and uncertainty". Socrates too pauses following this objection and then warns against misology, the hatred of argument.[22]

The Argument from the Form of Life

[edit]Socrates then proceeds to give his final proof of the immortality of the soul by showing that the soul is immortal as it is the cause of life. He begins by showing that "if there is anything beautiful other than absolute beauty it is beautiful only insofar as it partakes of absolute beauty".

Consequently, as absolute beauty is a Form, and so is Life, then anything which has the property of being animated with Life, participates in the Form of Life. As an example he says, "will not the number three endure annihilation or anything sooner than be converted into an even number, while remaining three?". Forms, then, will never become their opposite. As the soul is that which renders the body living, and that the opposite of life is death, it so follows that, "... the soul will never admit the opposite of what she always brings." That which does not admit death is said to be immortal.[23]

Socrates thus concludes, "Then, Cebes, beyond question, the soul is immortal and imperishable, and our souls will truly exist in another world. "Once dead, man's soul will go to Hades and be in the company of," as Socrates says, "... men departed, better than those whom I leave behind." For he will dwell amongst those who were true philosophers, like himself.[24]

The conception of the soul

[edit]The Phaedo presents a real challenge to commentators through the way that Plato oscillates between different conceptions of the soul.

In the cyclical and Form-of-life arguments, for instance, the soul is presented as something connected with life, where, in particular in the final argument, this connection is spelled out concretely by means of the soul's conceptual connection with life. This connection is further developed in the Phaedrus and Laws where the definition of soul is given as self-motion. Rocks, for instance, do not move unless something else moves them; inanimate, unliving objects are always said to behave this way. In contrast, living things are capable of moving themselves. Plato uses this observation to illustrate his famous doctrine that the soul is a self-mover: life is self-motion, and the soul brings life to a body by moving it.

Meanwhile, in the recollection and affinity arguments, the connection with life is not explicated or used at all. These two arguments present the soul as a knower (i.e., a mind). This is most clear in the affinity argument, where the soul is said to be immortal in virtue of its affinity with the Forms that we observe in acts of cognition.

It is not at all clear how these two roles of the soul are related to each other. But we observe this casual oscillation nevertheless throughout the dialogue and indeed throughout the whole corpus. For instance, consider this passage from Republic I:

Is there any function of the soul that you could not accomplish with anything else, such as taking care of something (epimeleisthai), ruling, and deliberating, and other such things? Could we correctly assign these things to anything besides the soul, and say that they are characteristic (idia) of it?

No, to nothing else.

What about living? Will we deny that this is a function of the soul?

That absolutely is.[25]

Throughout the 20th century, scholars universally recognized this as a flaw in Plato's theory of the soul, with this trend continuing and then ultimately being rejected in the 21st century.[26]

Here are some examples of what scholars have said about this puzzle:

- Sarah Broadie says that “readers of the Phaedo sometimes take Plato to task for confusing soul as mind or that which thinks, with soul as that which animates the body."[27]

- Dorothea Frede argued that “as to the exact nature of the soul we are left somehow in the dark by Plato in the Phaedo and also in Republic X."[28]

- D.R. Campbell argued that "Plato believes that the soul must be both the principle of motion and the subject of cognition because it moves things specifically by means of its thoughts."[29]

Legacy

[edit]Plato's Phaedo had a significant readership throughout antiquity, and was commented on by a number of ancient philosophers, such as Harpocration of Argos, Porphyry, Iamblichus, Paterius, Plutarch of Athens, Syrianus and Proclus.[30] The two most important commentaries on the dialogue that have come down to us from the ancient world are those by Olympiodorus of Alexandria and Damascius of Athens.[31]

The Phaedo has come to be considered a seminal formulation, from which "a whole range of dualities, which have become deeply ingrained in Western philosophy, theology, and psychology over two millennia, received their classic formulation: soul and body, mind and matter, intellect and sense, reason and emotion, reality and appearance, unity and plurality, perfection and imperfection, immortal and mortal, permanence and change, eternal and temporal, divine and human, heaven and earth."[32]

Texts and translations

[edit]Original texts

[edit]- Greek text at Perseus

- Plato. Opera, volume I. Oxford Classical Texts. ISBN 978-0198145691

- Plato. Phaedo. Cambridge Greek and Latin Classics. Greek text with introduction and commentary by C. J. Rowe. Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0521313186

Original texts with translation

[edit]- Plato: Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Phaedo, Phaedrus. Greek with translation by Harold N. Fowler. Loeb Classical Library 36. Harvard Univ. Press (originally published 1914).

- Fowler translation at Perseus

- Plato: Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Phaedo. Greek with translation by Chris Emlyn-Jones and William Preddy. Loeb Classical Library 36. Harvard Univ. Press, 2017. ISBN 9780674996878 HUP listing

Translations

[edit]- The Last Days of Socrates, translation of Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Phaedo. Hugh Tredennick, 1954. ISBN 978-0140440379. Made into a BBC radio play in 1986.

- Plato: Phaedo. Hackett Classics, 2nd edition. Hackett Publishing Company, 1977. Translated by G. M. A. Grube. ISBN 978-0915144181

- Plato. Complete Works. Hackett, 1997. Translated by G. M. A. Grube. ISBN 978-0872203495

- Plato: Meno and Phaedo. Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy. By David Sedley (Editor) and Alex Long (Translator). Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0521676779

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Lorenz, Hendrik (22 April 2009). "Ancient Theories of Soul". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- ^ I. F. Stone is among those who adopt a political view of the trial. See the transcript of an interview given by Stone here: http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/socrates/ifstoneinterview.html. For ancient authority, Stone cites Aeschines (Against Timarchus 173).

- ^ Duerlinger, James (1985). "Ethics and the Divine Life in Plato's Philosophy". The Journal of Religious Ethics. 13 (2). Blackwell Publishing Ltd: 322, 325, 329. ISSN 0384-9694. JSTOR 40015016.

- ^ Fletcher R., Platonizing Latin: Apuleius’s Phaedo in G. Williams and K. Volk, eds.,Roman Reflections: Studies in Latin Philosophy, Oxford University Press, 2015, pp. 238–259

- ^ See David Ebrey. 2022. Plato's 'Phaedo': Forms, Death, and the Philosophical Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Template:ISBN ?[page needed]

- ^ Plato, Phaedo, 57a–61c (Stph. p.)

- ^ Plato, Phaedo, 61d–62a.

- ^ Plato, Phaedo, 62b–65a.

- ^ Plato, Phaedo, 65e.

- ^ Plato, Phaedo, 65c.

- ^ Plato, Phaedo, 66a–67d.

- ^ Plato, Phaedo, 65e–66a.

- ^ Plato, Phaedo, 70a.

- ^ Plato, Phaedo, 69e–72d.

- ^ Frede 1978, 38

- ^ Plato, Phaedo, 72e–77a.

- ^ Plato, Phaedo, 78b–80c.

- ^ Plato, Phaedo, 81b.

- ^ Plato, Phaedo, 82d–85b.

- ^ Plato, Phaedo, 85b–86d.

- ^ Plato, Phaedo, 86d–88b.

- ^ Plato, Phaedo, 88c–91c.

- ^ Plato, Phaedo, 100c–104c.

- ^ Plato, Phaedo, 63c.

- ^ Plato, Republic, Book I, 353d. Translation found in Campbell 2021: 523.

- ^ See Campbell 2021: 524 n. 1 for more examples of scholars hurling this problem at Plato's feet, both in the English-language scholarship and abroad.[1]

- ^ Broadie, Sarah. 2001. “Soul and Body in Plato and Descartes.” Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 101: 295–308.[2] Quotation from p. 301

- ^ Frede, Dorothea. 1978. "The Final Proof of the Immortality of the Soul in Plato’s Phaedo 102a–107a". Phronesis, 23.1: 27–41.[3] Quotation from p. 38.

- ^ Campbell, Douglas (2021). "Self‐Motion and Cognition: Plato's Theory of the Soul." Southern Journal of Philosophy 59 (4): 523-544. Quotation is from p. 523.

- ^ For a full list of references to the fragments that survive from these commentaries, see now Gertz 2011, pp. 4–5

- ^ Both are translated in two volumes by L.G. Westerink (1976–77), The Greek Commentaries on Plato's Phaedo, vols. I & II, Amsterdam: North-Holland Pub. Co.

- ^ Gallop 1996, p. ix.

References

[edit]- Campbell, Douglas (2021). "Self‐Motion and Cognition: Plato's Theory of the Soul." Southern Journal of Philosophy 59 (4): 523–544.

- Crombie, Ian 1962. An Examination of Plato’s Doctrine, vol. 1. London: Routledge.

- Plato (1966) [1925]. "Phaedo, by Plato, full text (English & Greek)". Plato in Twelve Volumes. Translated by Harold North Fowler. Introduction by W.R.M. Lamb. Cambridge, MA & London, UK: Harvard University Press & William Heinemann Ltd.

- Long, Anthony A. 2005. “Platonic Souls as Persons.” In Metaphysics, Soul, and Ethics in Ancient Thought: Themes from the Work of Richard Sorabji, edited by R. Salles, 173–191. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Solmsen, Friedrich. 1955. “Antecedents of Aristotle’s Psychology and the Scale of Beings.” American Journal of Philology 76: 148–164.

- Gallop, David (1996). "Introduction". Phaedo. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. vii–xxiii.

- Trabattoni, Franco. 2007. “Si può di ‘unità’ della psicologia platonica? Esame di un caso significativo (Fedone, 69B-69E).” In Interiorità e anima: la psychè in Platone, edited by M. Migliori, L. Napolitano Valditara, and A. Fermani, 307–320. Milan: V&P Vita e Pensiero.

- Frede, Dorothea. 1978. "The Final Proof of the Immortality of the Soul in Plato’s Phaedo 102a–107a". Phronesis, 23.1: 27–41.

- Gertz, Sebastian R. P. (2011). Death and Immortality in Late Neoplatonism: Studies on the Ancient Commentaries on Plato's Phaedo. Leiden: Brill.

- Irvine, Andrew David (2008). Socrates on Trial: A Play Based on Aristophanes' Clouds and Plato's Apology, Crito, and Phaedo Adapted for Modern Performance. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-9783-5.

ISBN 978-0-8020-9783-5 (cloth); ISBN 978-0-8020-9538-1 (paper); ISBN 978-1-4426-9254-1 (e-pub).

Further reading

[edit]- Bobonich, Christopher. 2002. "Philosophers and Non-Philosophers in the Phaedo and the Republic." In Plato's Utopia Recast: His Later Ethics and Politics, 1–88. Oxford: Clarendon.

- Brill, Sara. 2013. Plato on the Limits of Human Life. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253008824

- Campbell, Douglas 2021. "Self‐Motion and Cognition: Plato's Theory of the Soul." Southern Journal of Philosophy 59 (4): 523–544.

- Dorter, Kenneth. 1982. Plato's Phaedo: An Interpretation. Toronto: Univ. of Toronto Press.

- Frede, Dorothea. 1978. "The Final Proof of the Immortality of the Soul in Plato's Phaedo 102a–107a". Phronesis, 23.1: 27–41.

- Futter, D. 2014. "The Myth of Theseus in Plato's Phaedo". Akroterion, 59: 88–104.

- Gosling, J. C. B., and C. C. W. Taylor. 1982. "Phaedo" [In] The Greeks on Pleasure, 83–95. Oxford, UK: Clarendon.

- Holmes, Daniel. 2008. "Practicing Death in Petronius' Cena Trimalchionis and Plato's Phaedo". Classical Journal, 104(1): 43–57.

- Irwin, Terence. 1999. "The Theory of Forms". [In] Plato 1: Metaphysics and Epistemology, 143–170. Edited by Gail Fine. Oxford Readings in Philosophy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Most, Glenn W. 1993. "A Cock for Asclepius". Classical Quarterly, 43(1): 96–111.

- Nakagawa, Sumio. 2000. "Recollection and Forms in Plato's Phaedo." Hermathena, 169: 57–68.

- Sedley, David. 1995. "The Dramatis Personae of Plato's Phaedo." [In] Philosophical Dialogues: Plato, Hume, and Wittgenstein, 3–26 Edited by Timothy J. Smiley. Proceedings of the British Academy 85. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Trabattoni, Franco (2023). From Death to Life: Key Themes in Plato's Phaedo. Brill. ISBN 9789004538221.

External links

[edit] Works related to Phaedo at Wikisource

Works related to Phaedo at Wikisource- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 341.

Quotations related to Phaedo at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Phaedo at Wikiquote- Phaedo, in a collection of Plato's Dialogues at Standard Ebooks

- Approaching Plato: A Guide to the Early and Middle Dialogues

- Guides to the Socratic Dialogues, a beginner's guide

- The grammatical puzzles of Socrates' Last Words

- "Plato's Phaedo". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Phaedo public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Phaedo public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Online versions

- Benjamin Jowett, 1892: full text

- George Theodoridis, 2016: full text